Gentle Reader,

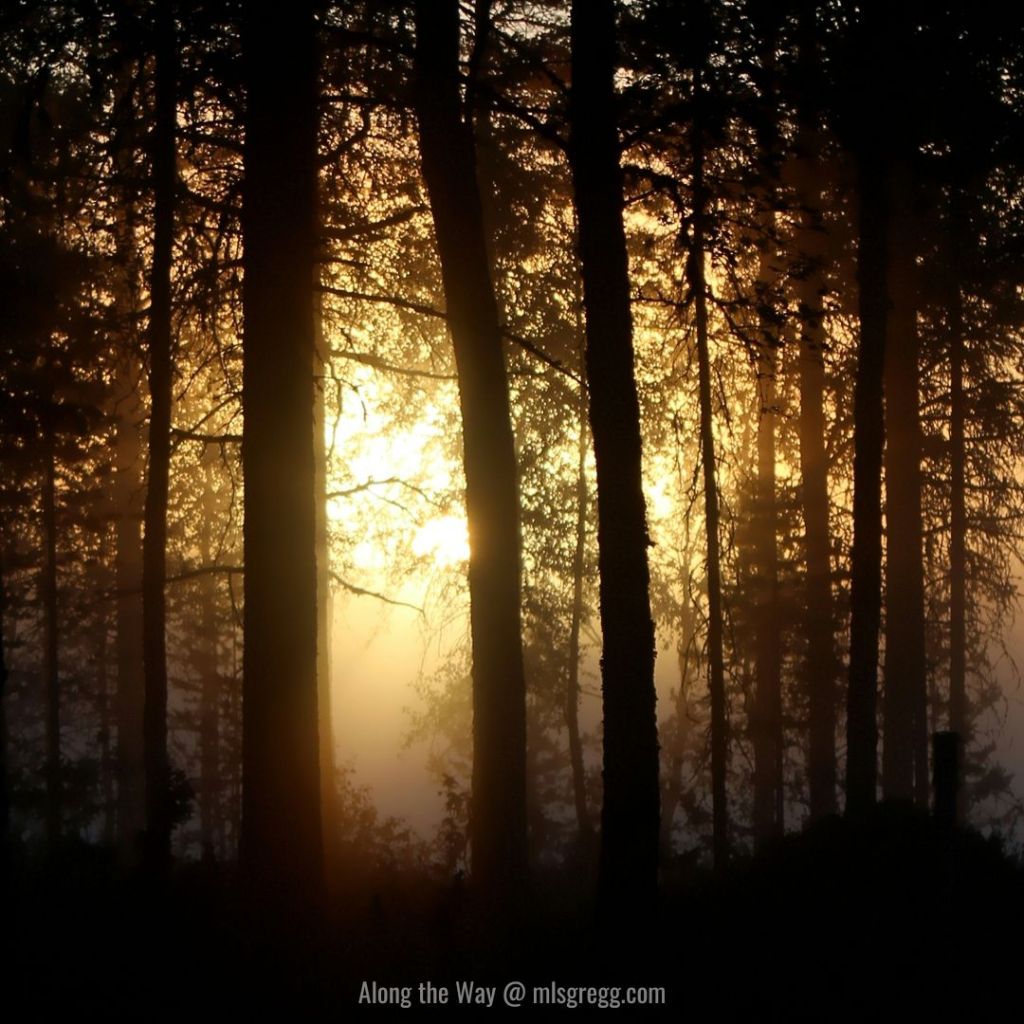

Attempting to explain or define holiness is sometimes like, as the good sisters of The Sound of Music tell us, pinning a wave upon the sand. You can see it. You can experience it. Trying to fully capture it… Maybe that’s part of the point. Maybe the just-out-of-our-grasp nature of holiness is what keeps us coming back. That would be very like God to do that.

Below is the third of three essays I wrote for my Doctrine of Christian Holiness class during my second year of seminary. May God grace you today with the desire to keep coming back to the holiness well that never runs dry.

********

Despite being the first song recorded for the project, “Tomorrow Never Knows” closes out The Beatles 1966 album Revolver. John Lennon’s composition follows hard on the heels of Paul McCartney’s “Got to Get You Into my Life,” a rollicking two minutes that leaves the listener with nothing but joy. This following, however, does not flow from a blending of the two songs, a mixing device growing increasingly common during that era. A full eight seconds of silence precedes the opening strains, prompting the listener to lean in. Eight seconds hardly seems like enough time to build tension, but tension builds, nonetheless. Finally, the distorted sound of a sitar and a hypnotic drumbeat fill the air, marking the piece as something altogether different from what has come before.

So, too, is the numinous altogether different. This way of attempting to use language in order to understand God and God’s nature, so fully entwined with the concept of holiness as to be inseparable from it, remains, in the end “inexpressible…ineffable – in the sense that it completely eludes apprehension in terms of concepts.” [1] In his book The Idea of the Holy, Rudolf Otto declares his preference for the term numinous, which pushes the reader to understand that holiness is not merely goodness. [2] Holiness encompasses goodness, but it is more than that, something which “cannot, strictly speaking, be taught, it can only be evoked, awakened in the mind.” [3] Holiness, as understood within the concept of the numinous, is not a state of doing, but a state of transcendent being, of connection with the fullness of divinity, of swimming in the unending depths of God’s love, something humanity only truly experiences when in right relationship with God. Just as “Tomorrow Never Knows” comes onto the scene as something completely different, something music lovers did not know they needed, so, too, does God. God is different, other, numinous.

One need go no further than the opening line of Scripture to be confronted with this reality. “In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth” [4] is not a scientific statement, but a theological one. The ancient author (or compiler) is looking to distinguish their belief system from that of the various polytheistic systems laced throughout Mediterranean and Mesopotamian cultures. Each of these religions had creation myths of their own, but their gods did not control nature or exist outside of it. Rather, their gods were often part of nature itself, [5] and it was necessary to appease each one in order to ensure survival in an agrarian world. Thus, the idea of a God, who created and controlled all of creation, would have left the ancients scratching their heads. What single god possessed that much power?

A sentence later, the Supreme Creator speaks into the chaotic void, splitting it open and ushering time into existence. “Then God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light.” [6] Easy enough to gloss over these familiar words, but the reader does well to sit with them. In just three short verses, humanity is confronted with complete otherness. What other being can create on such a scale? Who else holds the true power of life and death in their hands? If mediated upon, the sentences of the creation account produce a chill that shoots up the spine of the reader. They are encountering the Divine.

The numinousness of God does not end at creation, though. There are many examples in the New Testament, but arguably nothing more clearly points to the Divine otherness as well as the accounts of Jesus’ resurrection:

But on the first day of the week, at early dawn, they came to the tomb, taking the spices that they had prepared. They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, but when they went in, they did not find the body. While they were perplexed about this, suddenly two men in dazzling clothes stood beside them. The women were terrified and bowed their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, “Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen. Remember how he told you, while he was still in Galilee, that the Son of Man must be handed over to sinners, and be crucified, and on the third day rise again.” Then they remembered his words, and returning from the tomb, they told all this to the eleven and to all the rest. Now it was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women with them who told this to the apostles. But these words seemed to them an idle tale, and they did not believe them. But Peter got up and ran to the tomb; stooping and looking in, he saw the linen cloths by themselves; then he went home, amazed at what had happened. [7]

The resurrection of Jesus is usually understood as the miracle that seals the deal for humanity’s salvation. Jesus has done all that is necessary for God and humans to be in restored, right relationship. This is true, but this is not all that the resurrection means. Restoration is not its only statement. Upon exiting the tomb that could never hold Him, Jesus, both the subject and the expositor of a narrative line that begins in Genesis and continues throughout the entirety of the Bible, declares again that God is God and humanity is not. God is the Creator and the Sustainer of life. Nothing controls God, and God is not obligated to anyone. What God does, God does freely, and lovingly. [8]

What does this mean for a Christian who desires to live a life of holiness? Put all-too simply, the concept of numinousness directs the one who would follow God to remember God’s otherness. As “Tomorrow Never Knows” ushers in the distinct sound of psychedelic rock, ending one musical era and beginning another, an honest consideration of the otherness of God ushers in a profound reorientation for the one doing the considering. Life ceases to revolve around that which can be tasted, touched, smelled, or seen, and instead revolves around the One who called those senses into being. As such, holiness ceases to be defined by mere goodness, but is instead understood as a dynamic, life-giving way of being, created and sustained by the Creator and Sustainer.

[1] Rudolf Otto and John W. Harvey, The Idea of the Holy: an Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational (Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2010), 5.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Gen. 1:1.

[5] For example, ancient Israel regularly interacts with devotees of (and occasionally worship themselves) the god Ba’al, whose presence is seen in storms.

[6] Gen. 1:3.

[7] Lk. 24:1-12.

[8] Here I would like to explore the “God is love” motif, but the guidelines for this essay do not leave me room. Let the reader instead contemplate 1 Jn. 4:7-21 and understand that every action of God is a movement of love.

GRACE AND PEACE ALONG THE WAY,

MARIE

Image Courtesy of Anne Nygård

This song is theologically terrible, but musically great. Arguably, this is the first psychedelic rock piece. The way the guitars pierce your ears – I think holiness might be a bit like that at times.